Anywhere people have lived in forested areas, mythology and folklore about the woods co-exist with humanity. After all, before the internet and CNN, most of us perceived the nature of reality through the material world around us. As Marie-Louise von Franz writes in her classic The Interpretation of Fairy Tales:

Fairy tales are the purest and simplest expression of collective unconscious psychic processes. Therefore, their value for the scientific investigation of the unconscious exceeds that of all other material. They represent archetypes in their simplest, barest, and most concise form. In this pure form, the archetypal images afford us the best clues to the understanding of the processes going on in the collective psyche. In myths or legends, or any other more elaborate mythological material, we get at the basic patterns of the human psyche through an overlay of cultural material. But in fairy tales there is much less specific conscious cultural material and therefore they mirror the basic patterns of the psyche more clearly.

So what does von Franz write about the forest?

As von Franz would note, it depends on the tale. A longer answer might include one of the following depending on the tale.

- Entering the forest is the start of a journey that may lead to change for the protagonist.

- The forest can be considered a place of the unconscious and entering into it allows the protagonist to learn deep and meaningful lessons about themself and the world around them.

- As a place of refuge, the forest can be the place to escape from the human-created horrors of this world.

Or as von Franz writes in The Feminine in Fairy Tales,

The forest is the place where things begin to turn and grow again; it is a healing regression

Now if we were looking at folk tales from the American Southwest or Saharan Africa, the forest would not be intertwined in so many folk tales.

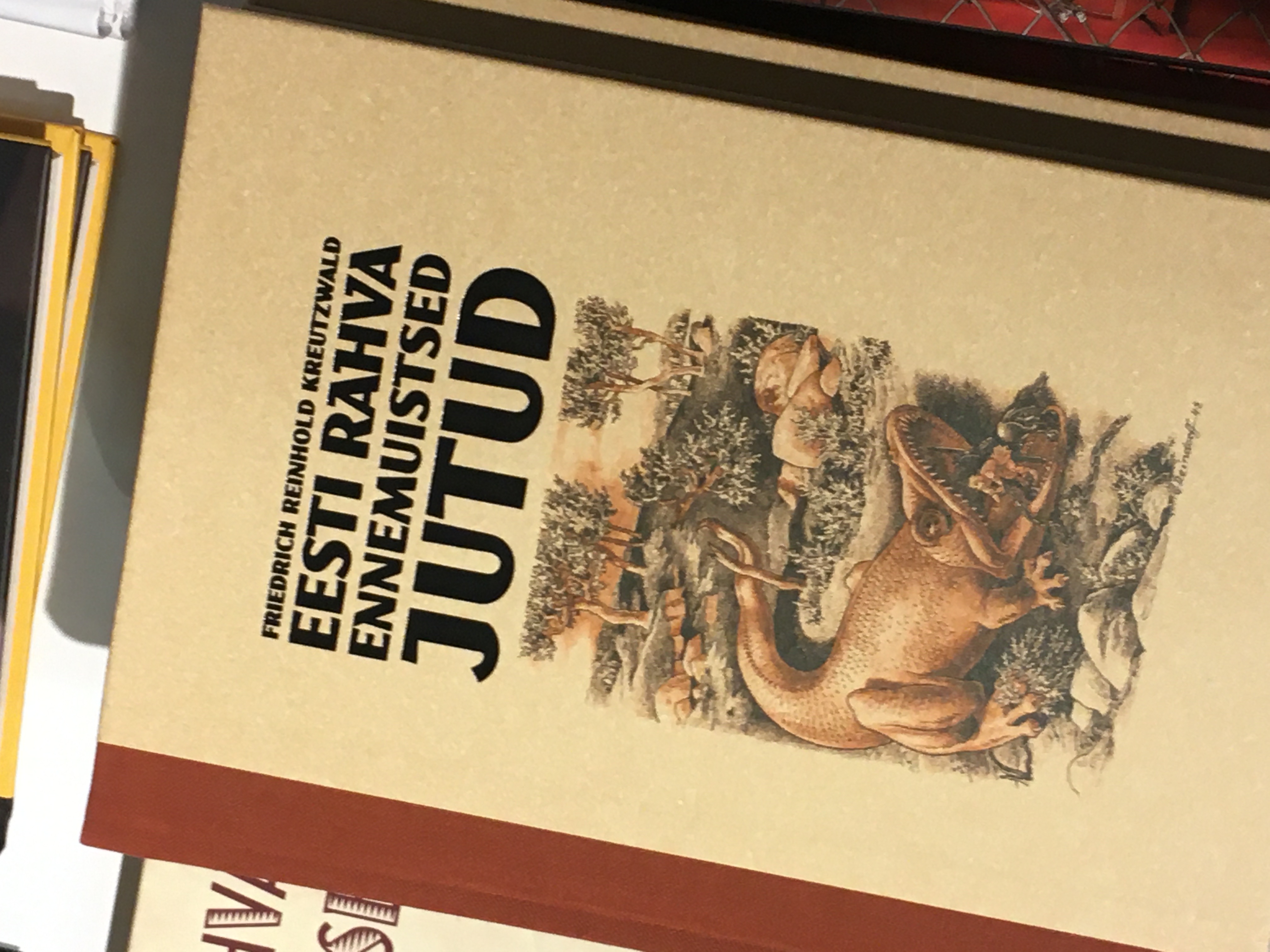

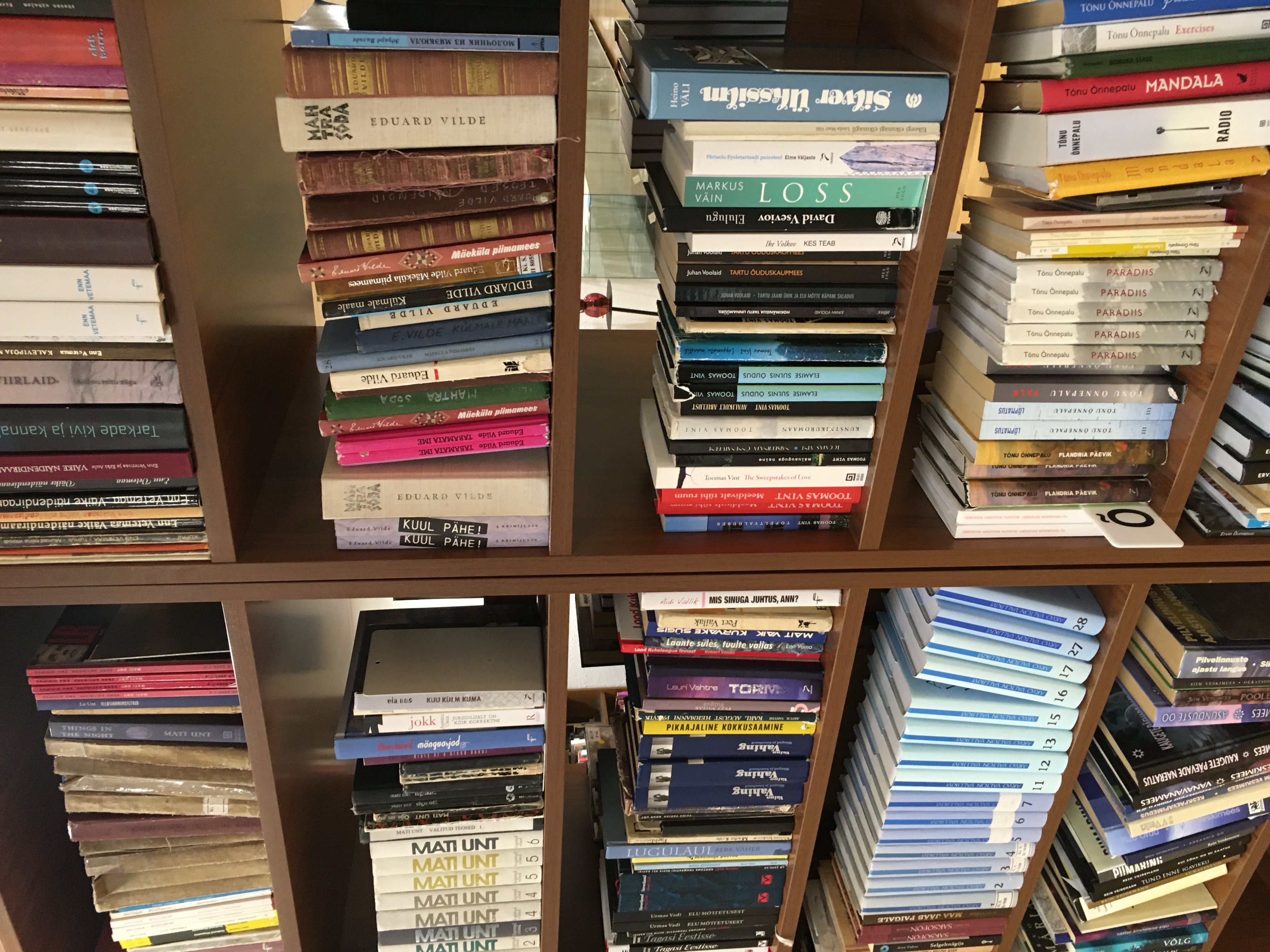

Yet analyzing the tales from northern Europe, and specifically Estonia, where trees grow like weed, the geography and ecosystems create an imaginal perspective with the forest as the place away from the village.

Depending on the era, this place of separation between the human constructed world and nature can be a positive experience or a fearful one. The forest can exist only to serve human material needs by providing wood for fires and building, animals for hunting, or berries for picking. But the forest in more modern times can serve a psychological need as a place to reconnect with the natural world.

How does the forest serve you? But even more importantly, how do you serve the forest?

How sad this makes me. How even now, thirty years after his death, the tears flow because he couldn’t or wouldn’t share it with me. Not knowing who my father was before I knew him is heart breaking and I think Estonia, being Estonian, or the tragedies that Estonia faced during his lifetime created a shadow that kept him from me.

How sad this makes me. How even now, thirty years after his death, the tears flow because he couldn’t or wouldn’t share it with me. Not knowing who my father was before I knew him is heart breaking and I think Estonia, being Estonian, or the tragedies that Estonia faced during his lifetime created a shadow that kept him from me.